Mor Polycarpus Geevarghese wasn’t just a bishop. He was the quiet force that kept thousands of Malayalee families from being pushed out of Karnataka in the 1960s. While politicians debated land rights and migration policies, he walked door to door in dusty towns, pulled children out of poverty, and built schools where none existed. He didn’t hold press conferences. He didn’t write books. But for over five decades, he changed lives - one family, one student, one meal at a time.

From Chennithala to Honnavar

Born M.P. George on April 5, 1933, in Chennithala, Kerala, he grew up in a family rooted in the ancient Syrian Christian tradition. He studied at Mangalore University, earned a BA (Hons), and then trained at Malecruz Dayro, a quiet monastery in Puthencruz where theology was taught in Syriac and lived in silence. By 1956, he was ordained as a deacon. A year later, he became a priest. But it wasn’t until 1962, when he was sent to Honnavar in Karnataka, that his true calling began.At the time, the Honnavar Mission - started in 1917 by Fr. George Pinto - was struggling. After the Indian government took over 32 mission schools in the 1940s, resources dried up. Malayalee migrants, who had moved north for work in the 1950s, were being pushed out. Local authorities questioned their right to stay. Their children, speaking only Malayalam, were left behind in crowded slums, unable to join schools or access basic services.

Fr. M.P. George didn’t wait for permission. He started feeding them. Then clothing them. Then teaching them. He opened a small school in a rented room. He made sure every child had a uniform, even if he had to buy it himself. He didn’t just teach math and English - he taught dignity.

The Eviction Crisis

In the late 1960s, the Karnataka government began pushing for the relocation of migrant communities. Malayalees were labeled “temporary workers.” Their homes were marked for demolition. Their children were told they didn’t belong.That’s when Mor Polycarpus stepped in.

He didn’t protest in the streets. He didn’t file lawsuits. He met with local officials. He showed them attendance records from his schools. He brought parents to meetings. He pointed out that these weren’t just migrants - they were taxpayers, shopkeepers, laborers, parents. He reminded them that the community had been in Karnataka for decades, long before the state’s current borders were drawn.

His approach worked. Not because he shouted, but because he was unshakable. He had proof. He had numbers. He had the trust of thousands. By 1975, the eviction orders were quietly dropped. The community stayed. And they thrived.

The Schools That Built a Future

Under his leadership, the Honnavar Mission grew from one small classroom to over a dozen institutions. He didn’t just open schools - he built libraries, hostels, medical camps, and vocational centers. He made sure girls were enrolled just as much as boys. He hired teachers from Kerala who spoke Malayalam, but also trained them to teach in Kannada and English.Former students still talk about how he’d show up at their homes in the evenings. Not as a bishop. As a man with a sack of rice or a new pair of shoes. “He’d sit on the floor with my mother,” one graduate recalled. “Ask her how much we spent on rent. Then he’d slip a note into her hand. ‘For your son’s books.’ No one else ever did that.”

By the 1990s, the mission was educating over 8,000 students annually. Church records show that membership in the Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church in Karnataka tripled during his tenure - not because of sermons, but because people saw a community that cared.

A Leader in Two Worlds

Mor Polycarpus was consecrated as Metropolitan on May 27, 1990, by Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I of Antioch. But his authority wasn’t just spiritual - it was social. He balanced two worlds: the ancient liturgy of the Syriac Church and the modern needs of a displaced community.He kept the old Syriac prayers alive in Sunday services. But he also made sure the homilies were in Malayalam and Kannada. He refused to let language become a barrier. He knew that if the children lost their mother tongue, they’d lose their identity. But if they couldn’t speak Kannada or English, they’d lose their future.

His leadership lasted 54 years - from 1957 until his death in 2011. That’s longer than most bishops serve. Most are moved every few years. He stayed. Because he believed the work wasn’t done.

Legacy in Stone and Story

When he died on March 6, 2011, at age 77, thousands lined the streets of Mangalore to pay their respects. His body lay in state at St. Anthony’s Jacobite Syrian Cathedral for two days. On March 9, he was buried beside the church he helped build.His successor, Mor Chrysostomos Markose, inherited not just a diocese, but a living institution - schools still running, hostels full, medical camps operating. The Honnavar Mission today still follows the model he created: education first, community second, faith always.

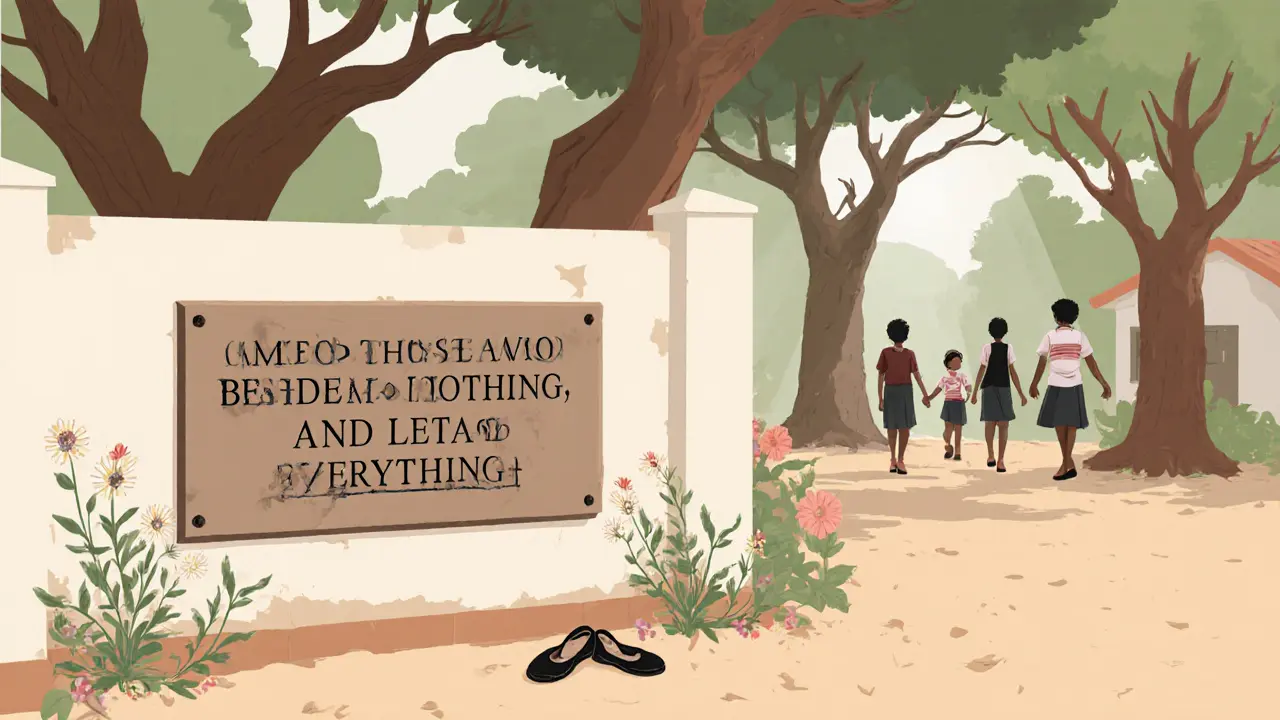

There’s no statue of him in the town square. No university named after him. But if you walk into any of the mission schools in Honnavar, you’ll see it - a small plaque near the entrance, barely noticeable. It reads: “For those who came with nothing, and left with everything.”

That’s his monument.

Why He Still Matters

In a world where leaders rise on speeches and social media, Mor Polycarpus reminds us that real change happens quietly. He didn’t need a title to lead. He didn’t need a platform to speak. He just showed up - every day - with food, books, and hope.His story isn’t just about a bishop. It’s about what happens when someone chooses to stand with the forgotten. When they refuse to let bureaucracy erase a community. When they turn a mission into a movement.

The Malayalee families in Karnataka didn’t just survive because of him. They became part of the fabric of the state. And that’s a legacy no law, no policy, no politician could ever undo.

Who was Mor Polycarpus Geevarghese?

Mor Polycarpus Geevarghese was a Metropolitan of the Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church who served the Evangelistic Association of the East (E.A.E) Arch Diocese from 1957 until his death in 2011. He was born in Kerala, ordained as a priest in 1957, and consecrated as Metropolitan in 1990. He is best known for his leadership of the Honnavar Mission in Karnataka, where he transformed it into a major center for education and social welfare for Malayalee migrants.

What did Mor Polycarpus do for the Malayalee community in Karnataka?

He protected thousands of Malayalee migrant families from forced eviction during the 1960s-1980s by negotiating with state authorities and proving the community’s long-standing presence. He built schools, hostels, and medical camps, ensuring children received education in Malayalam, Kannada, and English. He personally visited poor families to ensure kids attended school, and he provided food and clothing when needed. His work helped prevent the cultural and social fragmentation of the community.

How did he grow the Honnavar Mission?

When he arrived in 1962, the mission had lost most of its schools to government takeover. He started small - one classroom, then more. He raised funds locally and from Kerala. He hired teachers who spoke Malayalam but trained them in regional languages. He expanded into vocational training, hostels for girls, and medical outreach. By the 1990s, the mission operated over a dozen institutions serving more than 8,000 students annually.

Why was his leadership so long-lasting?

His 54-year tenure was unusually long for a Metropolitan. He earned deep trust from both the church and the community. He avoided political infighting within the church and focused on practical service. His calm, consistent presence made him a stabilizing force. Church historians say his diplomatic skills allowed him to navigate complex relationships between the Jacobite Syrian Church and the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate without losing focus on his mission.

Where is Mor Polycarpus buried?

He is buried at St. Anthony’s Jacobite Syrian Cathedral in Mangalore, Karnataka, where his body was laid in state for public viewing after his death on March 6, 2011. His funeral was held on March 9, 2011, and attended by thousands from across Karnataka and Kerala.

What is the current status of the Honnavar Mission?

The Honnavar Mission continues to operate under the E.A.E Arch Diocese of the Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church. It still runs schools, hostels, and community programs based on the model Mor Polycarpus established. While exact enrollment numbers aren’t publicly available, the institutions remain active and serve thousands of students annually, especially from low-income and migrant families.

paul boland

29 10 25 / 08:16 AMThis is the most ridiculous feel-good story I've ever read. 🤦♂️ Who cares if some bishop fed kids? Where's the evidence he didn't just use church money to buy votes? 🇮🇳🇮🇪 #FakeHero

harrison houghton

30 10 25 / 02:56 AMThere is a deeper truth here. This man didn't just build schools. He built bridges between the soul and the soil. He was a living sacrament of human dignity. In a world of algorithms and attention spans, he was the quiet pulse of what it means to be human.

DINESH YADAV

31 10 25 / 09:43 AMWhy is a Kerala bishop saving people in Karnataka? This is cultural invasion! We have our own poor. Why not help them? This is not charity, it's colonization with a cassock!

rachel terry

2 11 25 / 02:15 AMHonestly? This feels like a hagiography written by someone who never met a real bureaucrat. The idea that a single man could single-handedly stop state policy? Cute. But let's be real - it was probably a combination of political maneuvering, media pressure, and the fact that the community was already too entrenched to remove

Susan Bari

3 11 25 / 20:55 PMHe didn't save anyone. He just gave them a better place to be poor. Real change is systemic. This is just emotional bandaging wrapped in religious nostalgia

Marlie Ledesma

4 11 25 / 19:16 PMI cried reading this. The part about him slipping money to mothers on the floor... that’s the kind of love that doesn’t make headlines but changes generations. Thank you for sharing this.

Daisy Family

5 11 25 / 01:06 AMWow. So a priest did something nice. Big whoop. Next you'll tell me he didn't tax the parishioners or demand tithes in exchange for food. 😒

Paul Kotze

6 11 25 / 17:15 PMFascinating case study in grassroots social resilience. What's remarkable is how he leveraged cultural capital - language, religion, community trust - to navigate institutional resistance. His model is replicable: local knowledge + consistent presence + non-confrontational advocacy. The real lesson? Change doesn't require power. It requires patience.

Jason Roland

8 11 25 / 11:06 AMI get why people are skeptical, but look - this isn't about hero worship. It's about what happens when someone refuses to look away. He didn't wait for permission. He didn't need a grant. He just showed up. That’s the radical part.

Niki Burandt

8 11 25 / 19:54 PMLet’s be honest - this sounds like a church PR campaign. Who even *is* this guy? No Wikipedia page? No obit in The Hindu? And yet he’s some kind of miracle worker? 🤨 I smell saint-making. Also - why is he buried in Mangalore? He was from Kerala. That’s... odd.

Chris Pratt

10 11 25 / 04:49 AMAs someone who grew up in a migrant family, this hit me hard. He didn’t just help people - he gave them a home. That’s rare. I wish more leaders thought like this. Not with speeches. With shoes. With rice. With presence.

Karen Donahue

10 11 25 / 23:44 PMI find it deeply concerning that we glorify religious figures who operate outside the formal structures of governance. This isn't charity - it's the erosion of state responsibility. If you're feeding children, why isn't the government doing it? If you're building schools, why aren't you holding them accountable? This story is a dangerous distraction from systemic failure.

Bert Martin

11 11 25 / 13:25 PMYou don’t need to be a bishop to do this. You just need to care enough to show up. And that’s the real takeaway. We all have the power to be this person - even if it’s just one kid, one meal, one day.

Ray Dalton

12 11 25 / 03:06 AMThe part about him hiring teachers from Kerala but training them in Kannada and English? That’s genius. Language as identity + language as opportunity. He didn’t force assimilation. He built a bridge. That’s leadership.

Peter Brask

12 11 25 / 16:28 PMThis is all a setup. The church is using this story to distract from the fact that they’ve been quietly converting people under the guise of ‘education.’ And don’t get me started on the Syriac liturgy - it’s a cult relic. 🕊️💀 #ChurchControl